Fiche technique

Format : Broché

Nb de pages : 316 pages

Poids : 400 g

Dimensions : 22cm X 28cm

EAN : 9782503509471

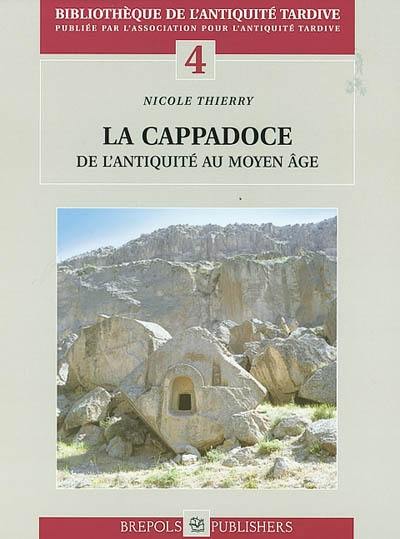

La Cappadoce de l'Antiquité au Moyen Age

Quatrième de couverture

La cappadoce de l'antiquité au moyen âge

La Cappadoce se compose de plusieurs régions et a subi des transformations répétées (Strabon XII, 1, 1). Cependant, on observe une permanence de son identité.

Histoire et archéologie témoignent des liens de la Cappadoce avec les régions voisines de Transcaucasie et de Mésopotamie septentrionale, l'ensemble faisant charnière entre le monde grec et iranien.

La rareté des villes explique la lente progression des civilisations dominantes, iranienne, hellénistique et gréco-romaine, byzantine puis turque.

Si les monnaies des rois de Cappadoce (302 av. J.-C. - 17 ap.) traduisent de l'hellénisation et de la romanisation de l'élite, le paganisme romain est caractérisé par la survie des entités mythiques hittites. On peut considérer comme exemplaire la popularité durable de la légendaire vision de saint Eustathe qui montre le Christ se révélant à lui sous la forme d'un cerf, dernier avatar du culte du cerf attesté en Anatolie hittite et romaine.

La découverte récente des nécropoles antiques et tombeaux monumentaux dans les zones rupestres connues pour leurs églises, ont mis en évidence la continuité du peuplement païen et chrétien. Pour la région d'Avanos-Goreme, l'archéologie confirme les données littéraires qui remontent à Strabon, aux Pères de l'Eglise et à une Vie de saint local écrite au début du VIe s.

La christianisation précoce de la province fut marquée par la fondation de l'Eglise d'Arménie dépendante de Césarée, et par le triomphe de l'Eglise cappadocienne à l'époque des deux Grégoire et de Basile le Grand. Dans les campagnes, il reste encore quelques-unes des nombreuses petites églises construites de cette époque au VIIe s.

Mais ce sont surtout les innombrables monuments rupestres et décors peints qui nous permettent de proposer une chronologie relative à partir du VIe s., de compléter des vides de l'imagerie chrétienne orientale et de juger de la byzantinisation des programmes cappadociens au XIe s..

Au cours du Haut Moyen Age, un art cappadocien gréco-oriental se développa caractérisé par la schématisation assyrienne des feuillages et rinceaux de vigne, transmise par les Sassanides, et qu'on retrouve dans toute l'aire méditerranéenne, en Transcaucasie et en Syrie omeyyade.

L'intense religiosité cappadocienne s'exprima par quelques images reflétant les discussions christologiques dont l'Iconoclasme fut la dernière crise. Après le hiatus dû aux guerres arabes, les fondations se multiplièrent et la créativité cappadocienne post-iconoclaste n'ignora aucun sujet (Déisis, Dormition, Transfiguration, Apôtres missionnaires et juges, éléments du Jugement dernier, etc.). La plupart de ces images n'eurent pas de suite byzantine alors qu'on retrouve des parallèles en Occident dans l'art carolingien, préroman et roman, et des échos orthodoxes dans la peinture géorgienne.

A Göreme, l'identification de la puissante famille des Phocas comme commanditaire de la Nouvelle Eglise de Tokali kilise (ca 950-960), et dans une église voisine, la représentation commémorative de leur triomphe, donnent vie aux épisodes glorieux de la reconquête des terres d'Asie.

Cappadocia from antiquity to the middle ages

`Cappadocia consists of several regions and has undergone repeated transformations' (Strabo, XII, 1, 1). Notwithstanding, Cappadocia did retain some continuity in identity through the ages.

History and archaeology both demonstrate the links that Cappadocia had with its neighbours in the Transcaucasus and northern Mesopotamia, all of which together formed a hinge between the Greek and Iranian worlds. The comparative lack of urbanisation explains why the civilisations took time to become established : Iranian, Hellenistic, Greco-Roman, Byzantine and then Turkish. Whereas the currency of the Cappadocian monarchs (302 BCE - 17 CE/AD) might show the transition at the elite level of Hellenic to Roman civilisation, Roman paganism can be characterised by survivals of elements from Hittite mythology. The longlasting popularity of the legend of St Eustathios's vision of Christ appearing to him in the form of a stag, a relic of the cult of the stag from Hittite and Roman Anatolia, is symptomatic of such survivals.

The recent discovery of ancient burial sites and monumental tombs in rocky areas known for their churches have reinforced the evidence for continuity between pagan and Christian settlement. In the area of Avanos-Göreme archaeology supports the literary evidence of writers such as Strabo, the Church Fathers and an anonymous Vita of a local saint written in the early sixth century. The very early Christianisation of the province was marked by the establishment of the Armenian Church dependent on Caesarea and the triumph of the Cappadocian Church during the period of the two Gregories and Basil the Great. In the countryside there still remain numerous small churches built between this period and the seventh century.

However, the innumerable rock monuments and painted decorations are the principal means for establishing a relative chronology from the sixth century onwards, for filling in the gaps in the imagery of Eastern Christianity, and to evaluate the degree of Byzantine influence in Cappadocian art in the eleventh century.

During the early Middle Ages a distinctive Cappadocian art developed which combined Greek and Oriental elements. It is characterised by the Assyrian style of depicting leaves and vines which came from the Sassanids and which is found throughout the Mediterranean, the Transcaucasus and in Omayyad Syria. The intense religiosity of Cappadocia is expressed in images which reflect the debates on Christology of which the last crisis was the Iconoclast controversy. After a gap caused by the Arab wars, new religious buildings multiplied and Cappadocian creativity after the period of the Iconoclast controversy knew no bounds ; painters covered subjects as diverse as the Deisis, the Dormition, Transfiguration, the apostles on mission and in judgement, and aspects of the Last Judgement. Many of these images were not followed-up in the Byzantine period even though we can find parallels in the West in Carolingian, pre-Romanesque and Romanesque art, and some Orthodox echoes in paintings from Georgia. At Göreme we know of the powerful Phocas family commissioning the New Church at Tokali kilise (c. 950-960), and in a nearby church a commemoration of their triumph, both of which locations bring to life glorious episodes in the reconquest of lands in Asia.