Fiche technique

Format : Broché

Nb de pages : 399 pages

Poids : 780 g

Dimensions : 17cm X 25cm

ISBN : 978-2-86803-078-8

EAN : 9782868030788

Les intellectuels bengalis et l'impérialisme britannique

Quatrième de couverture

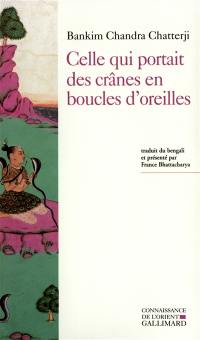

Trois intellectuels bengalis, Rammohun Roy que Nehru appela « le père de l'Inde moderne », Bhudev Mukherji, tout premier « sociologue » indien, Bankim Chandra Chatterji, romancier et essayiste, héritiers d'une des plus anciennes civilisations du monde, se trouvèrent confrontés à la domination britannique qui se fit de plus en plus pesante tout au long du XIXe siècle. Chacun d'eux réagit de manière différente, mais tous trois, bien que marqués par les acquis des Lumières, contestèrent la supériorité intellectuelle et morale de l'Europe au nom des philosophies de l'Inde, définirent la place de la religion dans la construction de leur future nation, engagèrent pour le premier, ou seulement acceptèrent pour les deux autres, des réformes religieuses et sociales tout en déniant au colonisateur le droit de s'immiscer dans la sphère privée. Ils s'interrogèrent sur la notion d'égalité, sur celle de progrès, sur la prééminence de la raison, la valeur de la tradition, la situation faite aux femmes et sur l'éducation qu'ils voulaient scientifique. Beaucoup des débats dont ils furent les initiateurs marquent encore l'Inde d'aujourd'hui.

Three Bengali intellectuals, Rammohun Roy whom Nehru called « the father of modem India », Bhudev Mukhopadhyay, the first « sociologist » in India, Bankim Chandra Chatterji, novelist and essayist, heirs to one of the most ancient civilizations in the world, were confronted with British imperialism that became more and more assertive all along the 19th century. Each of them reacted in a different way, but all three of them, though recognizing the contribution of Enlightenment, challenged the intellectual and moral superiority of Europe in the name of Indian philosophies, determined the place of religion in the construction of their future nation, started, as far as Roy is concerned, or simply accepted for the other two, religious and social reforms, nevertheless denying to the colonial government the right to interfere in the private domain. They examined the notion of equality, that of progress, the pre-eminence of reason, the value of tradition, the status of women and scientific education. Many debates that they initiated are not obsolete in independent and democratic India.